|

Mysterious red cells might be aliens!

By Jebediah Reed Popular Science Friday, June 2, 2006; Posted: 12:36 p.m. EDT (16:36 GMT) As bizarre as it may seem, the sample jars brimming with cloudy, reddish rainwater in Godfrey Louis's laboratory in southern India may hold, well, aliens.

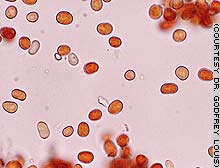

Specifically, Louis has isolated strange, thick-walled, red-tinted cell-like structures about 10 microns in size. Stranger still, dozens of his experiments suggest that the particles may lack DNA yet still reproduce plentifully, even in water superheated to nearly 600 degrees Fahrenheit . (The known upper limit for life in water is about 250 degrees Fahrenheit .) So how to explain them? Louis speculates that the particles could be extraterrestrial bacteria adapted to the harsh conditions of space and that the microbes hitched a ride on a comet or meteorite that later broke apart in the upper atmosphere and mixed with rain clouds above India. If his theory proves correct, the cells would be the first confirmed evidence of alien life and, as such, could yield tantalizing new clues to the origins of life on Earth. Last winter, Louis sent some of his samples to astronomer Chandra Wickramasinghe and his colleagues at Cardiff University in Wales, who are now attempting to replicate his experiments; Wickramasinghe expects to publish his initial findings later this year. Meanwhile, more down-to-earth theories abound. One Indian government investigation conducted in 2001 lays blame for what some have called the "blood rains" on algae. Other theories have implicated fungal spores, red dust swept up from the Arabian peninsula, even a fine mist of blood cells produced by a meteor striking a high-flying flock of bats. Louis and his colleagues dismiss all these theories, pointing to the fact that both algae and fungus possess DNA and that blood cells have thin walls and die quickly when exposed to water and air. More important, they argue, blood cells don't replicate. "We've already got some stunning pictures -- transmission electron micrographs -- of these cells sliced in the middle," Wickramasinghe says. "We see them budding, with little daughter cells inside the big cells." Louis's theory holds special appeal for Wickramasinghe. A quarter of a century ago, he co-authored the modern theory of panspermia, which posits that bacteria-riddled space rocks seeded life on Earth. "If it's true that life was introduced by comets four billion years ago," the astronomer says, "one would expect that microorganisms are still injected into our environment from time to time. This could be one of those events." The next significant step, explains University of Sheffield microbiologist Milton Wainwright, who is part of another British team now studying Louis's samples, is to confirm whether the cells truly lack DNA. So far, one preliminary DNA test has come back positive. "Life as we know it must contain DNA, or it's not life," he says. "But even if this organism proves to be an anomaly, the absence of DNA wouldn't necessarily mean it's extraterrestrial." Louis and Wickramasinghe are planning further experiments to test the cells for specific carbon isotopes. If the results fall outside the norms for life on Earth, it would be powerful new evidence for Louis's idea, of which even Louis himself remains skeptical. Skepticism greets claim of possible alien microbes

Jan. 5, 2006 A paper to appear in a scientific journal claims a strange red rain might have dumped microbes from space onto Earth four years ago. But the report is meeting with a shower of skepticism from scientists who say extraordinary claims require extraordinary proofãand this one hasn't got it.

"These particles have much similarity with biological cells though they are devoid of DNA," wrote Godfrey Louis and A. Santhosh Kumar of Mahatma Gandhi University in Kottayam, India, in the controversial paper. "Are these cell-like particles a kind of alternate life from space?" The mystery began when the scarlet showers containing the red specks hit parts of India in 2001. Researchers said the particles might be dust or a fungus, but it remained unclear. The new paper includes a chemical analysis of the particles, a description of their appearance under microscopes and a survey of where they fell. It assesses various explanations for them and concludes that the specks, which vaguely resemble red blood cells, might have come from a meteor. A peer-reviewed research journal, Astrophysics and Space Science, has agreed to publish the paper. The journal sometimes publishes unconventional findings, but rarely if ever ventures into generally acknowledged fringe science such as claims of extraterrestrial visitors. If the particles do represent alien life forms, said Louis and Kumar, this would fit with a longstanding theory called panspermia, which holds that life forms could travel around the universe inside comets and meteors. These rocky objects would thus "act as vehicles for spreading life in the universe," they added. They posted the paper online this week on a database where astronomers often post research papers. Louis and Kumar have previously posted other, unpublished papers saying the particles can grow if placed in extreme heat, and reproduce. But the Astrophysics and Space Science paper doesn't include these claims. It mostly limits itself to arguing for the particles' meteoric origin, citing newspaper reports that a meteor broke up in the atmosphere hours before the red rain. John Dyson, managing editor of Astrophysics and Space Science, confirmed it has accepted the paper. But he said he hasn't read it because his co-managing editor, the European Space Agency's Willem Wamsteker, handled it. Wamsteker died several weeks ago at age 63. A paper's publication in a peer-reviewed journal is generally thought to give it some stamp of scientific seriousness, because scientists vet the findings in the process. Nonetheless, the red rain paper provoked disbelief. "I really, really don't think they are from a meteor!" wrote Harvard University biologist Jack Szostak of the particles, in an email. And this isn't the first report of red rain of biological origin, Szostak wrote, though it seems to be the most detailed. Szostak said the chemical tests the researchers employed aren't very sensitive. The so-called cells are admittedly "weird," he added, saying he would ask his microbiologist friends what they think they are. "I don't have an obvious explanation," agreed prominent origins-of-life researcher David Deamer of the University of California Santa Cruz, in an email. They "look like real cells, but with a very thick cell wall. But the leap to an extraterrestrial form of life delivered to Earth must surely be the least likely hypothesis." A range of additional tests is needed, he added. Louis agreed: "There remains much to be studied," he wrote in an email. The researchers didn't dispute the panspermia theory itself, which has a substantial scientific following. "Panspermia may well be possible," wrote Lynn J. Rothschild of the NASA Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., in an email. "I'm just not so sure that this is a case of it." Others viewed the study more favorably. "I think more careful examination of the red rain material is needed, but so far there seems to be a strong prima facie [first-glance] case to suggest that this may be correct," said Chandra Wickramasinghe, director of the Cardiff Centre for Astrobiology at Cardiff University, U.K., and a leading advocate of panspermia. The story of the specks began on July 25, 2001, when residents of Kerala, a state in southwestern India, started seeing scarlet rain in some areas. "Almost the entire state, except for two northern districts, have reported these unusual rains over the past week," the BBC online reported on July 30. "Experts said the most likely reason was the presence of dust in the atmosphere which colours the water." The explanation didn't satisfy everyone. The rain "is eluding explanations as the days go by," the newspaper Indian Express reported online a week later. The article said the Centre for Earth Science Studies, based in Thiruvananthapuram, India, had discarded an initial hypothesis that a streaking meteor triggered the rain, in favor of the view that the particles were spores from a fungus. But "the exact species is yet to be identified. [And] how such a large quantity of spores could appear over a small region is as yet unknown," the paper quoted center director M. Baba as saying. Baba didn't return an email from World Science this week. The red rain continued to appear sporadically for about two months, though most of it fell in the first 10 days, Louis and Kumar wrote. The "striking red colouration" turned out to come from microscopic, mixed-in red particles, they added, which had "no similarity with usual desert dust." At least 50,000 kg (55 tons) of the particles have fallen in all, they estimated. "An analysis of this strange phenomenon further shows that the conventional atmospheric transport processes like dust storms etc. cannot explain" it. "The red particles were uniformly dispersed in the rainwater,≤ they wrote. ≥When the red rainwater was collected and kept for several hours in a vessel, the suspended particles have a tendency to settle to the bottom." "The red rain occurred in many places during a continuing normal rain," the paper continued. "It was reported from a few places that people on the streets found their cloths stained by red raindrops. In a few places the concentration of particles were so great that the rainwater appeared almost like blood." The precipitation, the researchers added, had a "highly localized appearance. It usually occur[ed] over an area of less than a square kilometer to a few square kilometers. Many times it had a sharp boundary, which means while it was raining strongly red at a place a few meters away there were no red rain." A typical red rain lasted from a few minutes to less than about 20 minutes, they added. The scientists compiled charts of where and when the showers occurred based on local newspaper reports. The particles look like one-celled organisms and are about 4 to 10 thousandths of a millimeter wide, the researchers wrote, somewhat larger than typical bacteria. "Under low magnification the particles look like smooth, red coloured glass beads. Under high magnifications (1000x) their differences in size and shape can be seen," they wrote. "Shapes vary from spherical to ellipsoid and slightly elongatedä These cell-like particles have a thick and coloured cell envelope, which can be well identified under the microscope." A few had broken cell envelopes, they added. The particles seem to lack a nucleus, the core DNA-containing compartment that animal and plant cells have, the researchers wrote. Chemical tests indicated they also lacked DNA, the gene-carrying molecule that most types of cells contain. Nonetheless, Louis and Kumar wrote that the particles show "fine-structured membranes" under magnification, like normal cells. The outer envelope seems to contain an "nner capsule," they added, which in some places "appears to be detached from the outer wall to form an empty region inside the cell. Further, there appears to be a faintly visible mucus layer present on the outer side of the cell." ≥One characteristic feature is the inward depression of the spherical surface to form cup like structures giving a squeezed appearance,≤ which varies among particles, they added. "The major constituents of the red particles are carbon and oxygen," they wrote. Carbon is the key component of life on Earth. "Silicon is most prominent among the minor constituents" of the particles, Louis and Kumar added; other elements found were iron, sodium, aluminum and chlorine. "The red rain started in the State during a period of normal rain, which indicate that the red particles are not something which accumulated in the atmosphere during a dry period and washed down on a first rain," the pair wrote. "Vessels kept in open space also collected red rain. Thus it is not something that is washed out from rooftops or tree leaves. Considering the huge quantity of red particles fallen over a wide geographic area, it is impossible to imagine that these are some pollen or fungal spores which have originated from trees," they added. "The nature of the red particles rules out the possibility that these are dust particles from a distant desert source," they wrote, and such particles "are not found in Kerala or nearby place." One easy assumption is that they "got airlifted from a distant source on Earth by some wind system," they added, but this leaves several puzzles. "One characteristic of each red rain case is its highly localized appearance. If particles originate from distant desert source then why [was] there were no mixing and thinning out of the particle collection during transport?" they wrote. "It is possible to explain this by assuming the meteoric origin of the red particles. The red rain phenomenon first started in Kerala after a meteor airburst event, which occurred on 25th July 2001 near Changanacherry in [the] Kottayam district. This meteor airburst is evidenced by the sonic boom experienced by several people during early morning of that day. "The first case of red rain occurred in this area few hours after the airburst... This points to a possible link between the meteor and red rain. If particle clouds are created in the atmosphere by the fragmentation and disintegration of a special kind of fragile cometary meteor that presumably contain[s] a dense collection of red particles, then clouds of such particles can mix with the rain clouds to cause red rain," they wrote. The pair proposed that while approaching Earth at low angle, the meteor traveled southeast above Kerala with a final airburst above the Kottayam district. "During its travel in the atmosphere it must have released several small fragments, which caused the deposition of cell clusters in the atmosphere." Alive or dead, the particles have some staying power, if the paper is correct. "Even after storage in the original rainwater at room temperature without any preservative for about four years, no decay or discolouration of the particles could be found."

|

In April, Louis, a solid-state physicist at Mahatma Gandhi University, published a paper in the prestigious peer-reviewed journal Astrophysics and Space Science in which he hypothesizes that the samples -- water taken from the mysterious blood-colored showers that fell sporadically across Louis's home state of Kerala in the summer of 2001 -- contain microbes from outer space.

In April, Louis, a solid-state physicist at Mahatma Gandhi University, published a paper in the prestigious peer-reviewed journal Astrophysics and Space Science in which he hypothesizes that the samples -- water taken from the mysterious blood-colored showers that fell sporadically across Louis's home state of Kerala in the summer of 2001 -- contain microbes from outer space. The shaded area represents the state of Kerala in India. (Courtesy Nichalp)

The scientists agree on two points, though. The things look like cells, at least superficially. And no one is sure what they are.

The shaded area represents the state of Kerala in India. (Courtesy Nichalp)

The scientists agree on two points, though. The things look like cells, at least superficially. And no one is sure what they are.